This story was reported by the Beacon Project, a student journalism initiative supported by the University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism to report on USC. It is independent of the university administration. Mark Schoofs, one of the project’s founders, is also an adviser to BuzzFeed News.

Year after year, for more than 20 years, young men who entered the University of Southern California student health center were sent to Dr. Dennis Kelly. Once the exam room door closed behind them, say 48 former patients who are gay or bisexual, Kelly subjected them to sexual abuse, such as fondling their genitals or making them kneel naked on the exam table for rectal probes. One man recalled that Kelly, without warning, inserted a metal instrument into his anus, then leaned forward and whispered, “How often do you let your partner cum in you?”

The men — all USC students at the time — were as young as 18, often struggling to accept their sexuality or uncomfortable discussing their sex lives.

At least five men say they complained to the university — far more than the single instance that has been previously reported — including one who described meeting face-to-face with the director of the health center specifically to warn her about Kelly. In addition, a person with direct knowledge of the matter, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that USC’s administration received even more complaints about the doctor’s inappropriate behavior with patients in the four years before Kelly departed USC in July 2018. Fifty former patients are now suing USC and Kelly, who has maintained that he always treated patients appropriately.

USC is already reeling from multiple high-profile scandals, including the nationwide admissions scam in which wealthy and high-profile parents were accused of paying bribes and committing fraud to get their children admitted. Now, the claims that USC was repeatedly warned about Kelly raise sharp questions about how the university investigated threats to its students’ well-being, and whether it has done more to protect its own reputation than the safety of its community members.

At the very same student health center where Kelly worked, USC had received numerous complaints of sexual misconduct with patients by the gynecologist George Tyndall — yet the university let Tyndall resign in 2017 with a payout and without alerting law enforcement or state medical authorities. In June, a federal court gave preliminary approval to a settlement, in which USC would pay $215 million to Tyndall’s former patients. Tyndall has been criminally charged with multiple felonies; he has pleaded not guilty.

In strikingly consistent accounts, the men who are suing Kelly allege “sexual battery,” “gender violence,” and “sexual harassment.” And they accuse USC of not doing enough to protect them, both through negligence and by concealing claims of sexual abuse and harassment. Of the five men who said they’ve complained to USC about Kelly, three said they’ve never heard back. One man said a USC official told him the incident occurred too long ago to determine what had happened. Another man said the university didn’t respond to his complaint for more than a year — until this February, after the first lawsuit was filed against Kelly and USC. Only then, he said, did the university reach out and acknowledge his complaint.

Kelly stopped seeing patients at USC in July 2018 and resigned the following month, according to a farewell email he sent to patients. In response to questions for this article, USC told the Beacon Project, a student journalism initiative to report on the university, that Kelly “personally initiated his resignation” and that he received no severance.

Kelly continued to treat students at nearby California State University, Northridge, as he had for years — and a Cal State Northridge official said that USC never alerted it to any problems about Kelly, or to the fact that he had resigned. Only when the first lawsuit was lodged against Kelly and USC — seven months after he had departed that institution — did Cal State Northridge halt his interactions with students and place him on paid administrative leave.

At his home in Santa Monica a short walk from the beach, Kelly, wearing a pinstripe bathrobe, declined to be interviewed. “This is all very traumatic to me,” he told a reporter before asking him to leave. Kelly did not respond to a list of detailed questions sent to him and his law firm, and a lawyer at the firm said it was not authorized to respond on his behalf. Kelly told the Los Angeles Times, which reported on the first six accusations, that he treated patients appropriately, saying, “I know I did it all professionally and without any other motive.”

Until this story, USC had made exactly one public statement about the accusations, saying in February that the university takes “this matter very seriously,” supports the LGBTQ community, and would “provide more information as it’s available.” The university declined to answer most questions for this article, citing ongoing litigation. Its guarded response has led some faculty members and editorial writers to accuse USC’s leadership of a disturbing pattern of stonewalling, in which the university ignores or actively hides problems until forced to respond. The school’s medical school dean was another such case: After complaints about Carmen Puliafito’s drinking, a woman overdosed while with him in a hotel room, where police found methamphetamine. USC gave the dean an $875,000 severance and let him resign quietly.

“USC treats litigation as an excuse for a level of secrecy that is not necessary,” said Ariela Gross, a law professor who is the chair of Concerned Faculty of USC, an influential group formed last year in the wake of the Tyndall scandal. “The university is not just a party in a lawsuit. The university is an educational community that owes something to all of its members.”

Others have lambasted USC’s recent decision to hire a lobbying firm to oppose a California state bill that would temporarily extend the statute of limitations for people who’ve experienced sexual abuse in student health centers. In an interview, the plaintiff known in court papers as John Doe 3 called the move a “calculated decision to continue this cloak of secrecy.”

USC did not respond to questions about whether it raised concerns about Kelly to the Medical Board of California, which licenses physicians. A spokesperson for that body said that all complaints and investigations are kept confidential until a formal accusation is filed through the state attorney general’s office. Kelly’s profile on the Medical Board website shows that his physician’s license is valid, and no public accusations are listed.

“The university is committed to providing all patients, students, faculty and staff with a culture of respect and support” said a statement provided by USC for this story, including links to support services. In an interview, Michael Blanton, USC’s vice president of professionalism and ethics, flatly denied that the university put concerns such as its reputation above student safety. In the wake of the Tyndall scandal, the university has implemented what it calls “sweeping changes to restore trust and heal our community,” including hiring new staff members and creating a new office to monitor and investigate complaints about misconduct.

Noting that the allegations in the Kelly lawsuits are “serious,” the university said it is important to continue “fact-finding in the most complete manner possible” and pledged it “will communicate information, to the extent possible, to affected communities as cases make their way through the court process.”

USC is being represented by the same law firm — Fraser Watson & Croutch — that is defending Kelly. Neither USC nor the law firm responded to questions about why the firm is representing both parties and whether USC is paying for Kelly’s defense. California law requires employers to pay for the legal defense of employees sued for carrying out their duties.

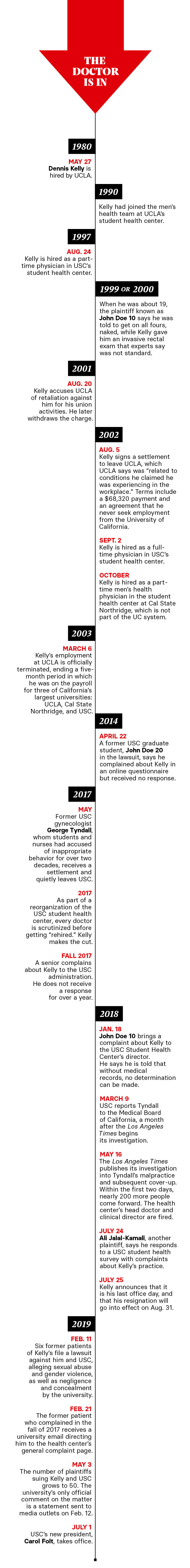

Even as USC’s handling of the complaints about Kelly is coming under new scrutiny, documents obtained exclusively by the Beacon Project show that 17 years ago, another major university — the University of California, Los Angeles — severed ties with Kelly through a confidential settlement.

Kelly had started work at UCLA’s student health center by 1990, specializing in men’s health. In 2002, UCLA and Kelly reached an agreement, which was obtained by the Beacon Project through a public records request. The agreement halted the doctor’s clinical responsibilities but kept him on the university’s payroll for seven more months after he stopped working and paid him a lump sum of $68,320.

It could not be determined what exactly led to the settlement. In response to questions, a UCLA spokesperson said it was related to conditions Kelly “claimed he was experiencing in the workplace.” Public records show that Kelly had accused UCLA of retaliating against him for union activities, and an excerpt from an employee evaluation described him as “unhappy and dissatisfied” at work. Kelly’s attorneys declined to comment, and Kelly did not respond to written questions sent to his home.

The settlement bound UCLA and Kelly to secrecy: Neither party could make “any derogatory or disparaging statements to any other person or third parties about each other,” and UCLA could not tell future employers anything about Kelly except to confirm his title, pay, and dates of employment at UCLA. Kelly was also barred from ever seeking employment at any college within the University of California system.

Just one month after signing the settlement agreement, Kelly, who had already been working at USC on an hourly basis for five years, was hired on staff there. A month later, he landed his part-time job at Cal State Northridge. While also funded by the state of California, Cal State Northridge is part of an educational system separate from the University of California.

Make more work like this possible by becoming a BuzzFeed News member today.

No one from UCLA or Cal State Northridge is known to have publicly accused Kelly of misconduct. Whether UCLA ever communicated with the two other universities about Kelly is unknown: Officials at USC and UCLA did not respond to the question. A spokesperson for Cal State Northridge, citing confidentiality restrictions, said it could not comment.

The person who ran UCLA’s student health center in 2002 and signed Kelly’s settlement agreement was Dr. Edward Wiesmeier, who has since retired. In interviews, he said Kelly’s evaluations were “not glowing” but repeatedly said he either didn’t recall or wouldn’t comment on the settlement.

At his hilltop house outside San Diego, Wiesmeier spoke through a barred window in his door. He said that last year — 16 years after Kelly and UCLA parted ways — two attorneys from the university showed up at his home. They questioned him for about two hours because, he said, “something was cooking with Dr. Kelly.” He would not say anything more about what the lawyers asked or what he told them. Neither UCLA nor Kelly’s lawyers responded to written questions about the lawyers’ visit.

In all, Kelly has treated young men at three of California’s largest universities, which currently have a combined student population of more than 130,000.

A consistent pattern

For this story, the Beacon Project examined court papers for all 50 plaintiffs, interviewed 10 of them in phone calls coordinated by their attorneys, spoke with another two men who are not suing but say Dr. Kelly mistreated them, and reviewed medical records, emails, and other documents. All but one of the men spoke on the condition they remain anonymous.

Taken as a whole, the men’s allegations describe a harrowing and consistent pattern of abuse by Kelly.

When a patient came in for a general checkup, STD testing, or a consultation on how to prevent HIV infection, the appointment nearly always began with an interrogation into the young man’s sexual history. Using crude terms such as “dick,” “pussy,” and “asshole,” Kelly would ask his patient questions that seemed to have no medical purpose: Where did they have sex? Did they watch porn? What dating apps did they use? What race were their partners? And, in one case, what were their partners’ names? Many students said they felt shamed, and some gay and bisexual students said they felt Kelly’s questions and comments were stigmatizing. Kelly himself is openly gay.

Kelly’s questions, the men say, were often followed by an instruction to undress. Kelly did not turn around or leave the room as the men took off their clothes, they said, and he almost never told patients why they needed the exam he was about to give, or that they could decline it. As the young men waited on the examination table on their hands and knees, facing the wall, Kelly would examine them, usually in complete silence. He would insert his fingers or a device into their rectums — almost always without warning — and keep it inside them for up to several minutes. When one patient winced in pain, Kelly told him he needed to “learn how to relax.”

At least 23 former patients said in court papers that Kelly fondled their penises as part of his examination. These exams, the men said, made them feel anything from “distressed” to “violated.”

Kelly has defended his practice, telling the Los Angeles Times that he looked away or exited the room when his patients undressed, and that it was standard for a doctor to take a rectal swab while simultaneously checking for anal warts.

But the Beacon Project spoke to four doctors: Robert Goldstein, an LGBTQ health specialist from Harvard; Howard Heller, a 22-year veteran physician at MIT; Jeffrey Klausner, a professor of medicine at UCLA and the author of a textbook on STDs; and Revery Barnes, an HIV specialist for Los Angeles County. Without medical records, they said they could not comment on any specific patient’s care. But they said the men’s allegations — especially given how many there were and the consistency among them — raised what Barnes called “large red flags.”

STD tests rarely require probing inside the rectum — a quick swab or a visual inspection almost always suffices. Kelly occasionally told his patients he was testing them for prostate health, but the American Urological Association does not recommend routine prostate cancer screening for men under 40, and most of Kelly’s patients were students in their twenties or late teens. Before conducting an invasive exam, experts say, doctors should ask patients if they consent, and if patients agree to the procedure, doctors should explain what they’re doing and check in frequently to make sure patients are comfortable every step of the way.

Kelly’s actions caused lasting damage, several patients said. One man said Kelly’s comments poisoned a relationship he was in. Another said he felt so violated by the rectal exam that he fell into an emotional tailspin lasting more than two years, in which he gained 70 pounds and his grades plunged.

Five men allege in court documents that they cried during or after their exam, and at least 13 said they avoided the health center after seeing Kelly. Many others said they felt horrified or humiliated, such as the student who recalled Kelly administering the rectal probe and leaning down to ask how often his partners came inside him. “And after that, it’s a blackout,” the student said. “I don’t even remember leaving his office, I don’t remember how I got home. I was just shocked by how creepy it was, the whole situation.”

In the case of Tyndall, the gynecologist who worked for decades in the same student clinic as Kelly, USC let him resign with a payout despite a damning report — commissioned by USC itself — that documented sweeping allegations of “unprofessional, inappropriate, and/or unusual” behavior (including keeping photographs of female students’ genitals, inserting his fingers into patients’ vaginas during exams, and commenting that his patients’ breasts were “perky” or their pelvic muscles “tight”). His case came to light only because of stories published by the Los Angeles Times.

After the departure of the medical school dean with drug problems, USC named Rohit Varma as his replacement. But he had to resign after it came out that he had been reprimanded for sexually inappropriate behavior in 2002 with a student — who had received a payout of more than $120,000 from the university.

USC’s medical school suffered another humiliating blow in April when a cardiovascular fellowship it sponsored together with Los Angeles County had its accreditation revoked. At the same time, the accreditation of the entire medical school was placed on probation, an extraordinarily rare penalty.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education did not state the reason for such strong discipline. But the action came on the heels of accusations that USC had failed to adequately investigate reports of sexual assault in the cardiovascular fellowship, and the medical school dean told faculty members that the penalty was imposed because of concerns about the “safety and wellness processes” for medical school residents. Responding to questions for this story, a spokesperson for USC said that once it became aware of the sexual assault allegations, it “took appropriate actions.”

Concerning Kelly, the men who say they complained to USC say the incidents cover a span of almost two decades, from shortly after he began treating students at the university to his last days on the job in 2018.

Engemann Student Health Center on the campus of the University of Southern California.

A face-to-face meeting

Kelly, now 73, received his medical degree from the University of Pittsburgh in 1972 and was licensed by the Medical Board of California two years later. University records list him as a clinical instructor in USC’s Department of Emergency Medicine from 1979 to 1981, and a Los Angeles Times article from 1989 identified him as the chief of emergency services at Valley Presbyterian Hospital in Van Nuys.

He joined USC’s student health center in 1997, working part time on the new men’s health team. Not long after that, an undergraduate came to Kelly’s office for a sexual health exam. He had been told that Kelly was “the best person to provide health guidance and/or anything else specialized to gay men.” Now identified in court papers as John Doe 10, the man said that he doesn’t remember if the appointment was in 1999 or 2000, and that USC told him it doesn’t keep records from that far back. But he said he vividly remembers what happened in the exam room.

Kelly said he needed to check the student’s prostate health even though the student said he had no symptoms. The doctor told the patient to pull down his pants and underwear and get on his hands and knees on top of the examination table. Kelly, the patient said in court documents, did not turn around or leave the room while the man undressed.

Then, he said, Kelly inserted a finger into his rectum and placed pressure on his prostate until his penis released fluid, which Kelly collected onto “some sort of a slide.” Kelly told his patient that the fluid would be sent to a laboratory for “testing,” he said.

The four doctors consulted for this article said that for patients with no symptoms, a procedure of this kind is not a standard part of a prostate exam.

The student said he didn’t know that. All he knew was that something was off. He said he continued to see Kelly “because he was the only doctor that specialized in men’s health” but “he always made me feel really uncomfortable, and I always felt like he was kind of creepy.”

Years later, he recounted his experience with Kelly to his primary care physician, who explained to him that doctors “don’t start even thinking about checking for prostate health until you’re over the age of 40.”

That conversation put his experience with Kelly in a new light. Later, when the man read about the scores of victims of former USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar, who had worked in the Michigan State University student health center, he decided to take action.

As a staff member at USC, he was in a particularly good position to do so. He said he met face-to-face with USC’s head of student health, Dr. Sarah Van Orman, in her office on Jan. 22, 2018. He said Van Orman took written notes.

As corroboration for his story, the man shared an email he had sent to his physician on the day he contacted the student health center to complain. In that email, he reminded his doctor about the “weird” prostate exam he’d had years ago, said it still “upsets me for many reasons,” and added, “I did go speak to someone at the USC Health Center earlier today and they will follow up with me.”

Van Orman declined to comment on the man’s account. She referred the question to a USC spokesperson, who also declined to comment. Van Orman did stress that USC has taken steps to improve student health services. When she took over in August 2017, she said, the health center was integrated into USC’s Keck School of Medicine, which tracks all complaints. At the same time, she said, every physician in the student health center was “hired anew” using Keck’s process for evaluating physician qualifications, which is now used for all new hires at the health center. During the rehiring process, she said, no health center staff members were let go.

About two weeks after his meeting with Van Orman, the man said, she called him and told him that a review had been conducted, and that Kelly, who was still on staff at the time, had said that without access to the medical records from the long-ago visit, there was no way to determine whether the examination was necessary.

“She basically thanked me for coming forward and letting them know, because this would be helpful to them if a pattern was being seen,” he said.

Silence for more than a year

On Feb. 27, 2017, a first-year student saw Kelly for STD and HIV screening. Kelly, the student claimed, started asking questions “about my sex life, which I understood, because, you know, sexual health doctor.” But Kelly kept on pressing for details. “It was just very uncomfortable,” the student said in an interview, and Kelly was “rude the entire time.”

Then Kelly took him into an examination room. The student, now a senior at USC, said that he has since had other STD screenings and that Kelly “did things that other doctors haven’t,” things that were “intrusive.” “I don’t really want to go into detail,” he said.

Months later — the student thinks it was the next semester — he told Kelby Accardi-Harrison, the director of USC’s LGBT Resource Center, about his experience. She had heard similar complaints about Kelly, he recalled her saying, and had always reported them to the university.

Accardi-Harrison confirmed that the student brought the complaint to her and that she reported it up to USC’s administration. She said she couldn’t comment further, citing the ongoing lawsuits.

Then, nothing happened. For more than a year, the student said, he did not receive any communication at all from the university about his complaint.

Dr. George Tyndall at Los Angeles Superior Court in Los Angeles.

But just 10 days after the first suit against Kelly and USC was filed, the student — who has not joined any legal action — received an email from the university’s Office of Conduct, Accountability, and Professionalism. The message thanked him for his complaint and directed him to a webpage with counseling and support services. That page mentions Tyndall, the gynecologist accused of abusing hundreds of patients, but even now does not mention Kelly.

A month later, while away on spring break, the student received a voicemail from a former Los Angeles Police Department sex crimes detective, Ninette Toosbuy, who is now a senior investigator for USC’s accountability office. In that voicemail, reviewed by the Beacon Project, Toosbuy identifies herself as an investigator and asks the student to contact her.

The student said he called back, telling her that he preferred not to discuss the matter while on vacation. He said he did not try to contact Toosbuy again and never got another call from her. Asked for this story about why she did not follow up, Toosbuy said it was “something that fell through the cracks and was quite nondeliberate.”

No follow-up

Around November 2012, John Doe 20 was a graduate student. Married but in an open relationship, he said he saw Kelly for a routine sexual health appointment. Kelly asked him “invasive and uncomfortable questions,” the man said in court papers, including how much porn he watched and what kind. Asked how he met men, John Doe 20 said through dating apps. But Kelly, he said, wasn’t satisfied with that answer, and replied, “I need to know which ones.” Kelly, the man said, also asked how many people he had slept with — and after hearing his answer, exclaimed, “Wow. That is the highest number of sexual partners of any of my other patients.”

Even though John Doe 20 had no symptoms, he said Kelly gave him a “prolonged” exam of his penis and testicles. The doctor, he said, remarked on the fact that John Doe 20 was uncircumcised and pulled back his foreskin. Kelly, the man said, then administered a prostate exam with his finger for 45 seconds to a minute and then, without warning, inserted a device into his anus. At the time, the man was about 25 years old.

The man was so upset, he said, that he sent an email to the student health center, asking how to file a grievance — but never heard back.

About a year and a half later, in 2014, the man received a link to an online survey about the student health center, which he said he filled out. Asked what he wrote five years ago, the man replied that he described how Kelly gave “moralistic responses to my sexual behavior, often shaming me for not being in a monogamous relationship” and that Kelly “would ask seemingly invasive questions about my sex life and how I choose to meet partners.” After he submitted the survey, he said the system thanked him for his submission, but he never received a follow-up or noticed any changes in Kelly’s behavior during subsequent visits.

John Doe 6, as he is called in court papers, was an 18-year-old first-year student when he saw Kelly for his first-ever STD check in December 2008.

Like so many of Kelly’s patients, he said he felt shamed and humiliated by the doctor’s questions, such as whether he ever watched internet porn, and his comments, such as calling unprotected sex “dirty.” The first-year student said he told Kelly that he had no symptoms or concerns related to STDs — but Kelly nevertheless insisted that he get on all fours on the exam table and, without any explanation of what to expect, penetrated him with an instrument, his fingers, or both for about a minute.

Afraid of seeing Kelly again, the man said he told personnel at the student health center that he wanted a different doctor, and on Aug. 17, 2009, he saw Dr. Kevin Kwak, who was then another student health physician.

“I went in there expecting to get groped and fingered again,” the patient said in an interview. To his surprise, Kwak didn’t even ask him to undress, which led to a conversation in which the patient described the rectal exam Kelly had administered. Kwak, the patient said, “just gave me this look and he’s like, ‘Well, that shouldn’t have happened.’ And that was the end of it.”

“I really thought that there would be some kind of follow-up,” the former student continued. “I really just figured if I brought it up to the right person and told them what happened, then something would happen about it — you know, there’s justice in the world, or whatever. But his reaction was just, again, one of confusion and sort of dismissal. Like, once it was over, it was over.”

“I feel awful that that was the student’s experience and interpretation of my response,” Kwak, who is now a part-time physician at Cal State Northridge, wrote via email. The doctor said he has “no specific recollection of this visit. However, in general I don’t recall ever having any concerns or being alarmed about the appropriateness of Dr. Kelly’s medical care.”

“A very negative impact”

Ali Jalal-Kamali, a doctoral candidate in USC’s Viterbi School of Engineering, said he went to see Kelly in the fall semester of 2017 to get a prescription for PrEP, the once-a-day pill that is very effective in preventing HIV infection. But, he recalled in an interview, “it was so uncomfortable from my very first conversation.”

Kelly asked “prying” questions, the graduate student said in court papers, including about the ethnicity of his partners. Jalal-Kamali said he wasn’t comfortable answering, but Kelly, he recalled, responded that if he wanted Kelly’s help, he would have to answer. “I just didn’t know what a doctor is allowed to ask and not ask, because I come from a different culture,” said Jalal-Kamali, who is from Iran. He submitted to more questions, he said, but even so Kelly wouldn’t give him PrEP, saying that to get the prescription he would have to come back for more appointments.

Joshua O’Neal, director of sexual health services at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, said that the only reason his organization would delay prescribing the medication is if a patient has certain conditions, such as kidney problems, that PrEP can exacerbate, or had already contracted HIV, in which case PrEP would be useless. In general, he said, if patients request the medication, doctors “should get them on PrEP immediately.”

At least eight other patients said that Kelly imposed impediments to obtaining PrEP, such as requiring them to come back multiple times and even subjecting them to additional rectal examinations — something experts said makes no sense.

Jalal-Kamali said he saw Kelly several more times. Twice, he said, Kelly pushed him to have a rectal exam, which the graduate student said he refused. But he said Kelly did examine his penis — “he started playing with my genitals for an extended period of time,” Jalal-Kamali recalled in an interview, “and I was so uncomfortable.”

During the appointments, Kelly continued to ask all kinds of questions about the man’s sex life, sometimes with a “very creepy smirk on his face,” Jalal-Kamali recalled. The graduate student remembers one of Kelly’s comments, which struck him as racist: “So you are into black guys? But you are a top.”

Jalal-Kamali told Kelly that he had met his partner on Grindr, a gay dating and hookup app. Kelly, the graduate student recalled, responded that “everyone on Grindr sleeps with everyone else” and warned that his partner “could not be trusted.” Later that semester, after his partner tested positive for an STD, Jalal-Kamali said that Kelly admonished him by saying, “I told you not to trust those people.”

Jalal-Kamali said Kelly’s comments “had a very negative impact” on his relationship, which he eventually ended. “I started really disliking [my ex] because of everything that Dennis Kelly told me,” he said. “I became really paranoid about if he lied to me or not.”

On July 24, 2018, the day before Kelly announced his resignation, Jalal-Kamali received a survey invitation from USC Student Health. He said he submitted an online response complaining about Kelly. In an interview, Jalal-Kamali said he wrote something along the lines of: Kelly “is not professional, the questions that he asked and his conduct is inappropriate. I felt very uncomfortable in his office, I’ll never go to him.” He does not remember if he included his name on the survey and said he did not receive a response.

Kelly’s last day in the office was July 25, 2018, according to an email he sent his patients that day. “It has been a privilege to have been your doctor and your partner in health,” he wrote in the email. The doctor said his resignation would go into effect Aug. 31.

John Doe 1 photographed in Los Angeles on Aug. 2, 2019.

“It really did take a lot out of me”

Some patients said the effects of Kelly’s actions reverberated for years. The very first man to sue, John Doe 1, saw Kelly on Dec. 10, 2009, the semester he transferred to USC. In response to Kelly’s questions, the man repeatedly said that he had never had anal sexual contact, and had not been sexually active at all since his last checkup. Nevertheless, he recalled, Kelly insisted that he needed a rectal exam.

On all fours, he felt Kelly suddenly insert something into his anus, which was “really painful,” and he said Kelly told him he needed “to learn how to relax.” The exam “was not just in and out real quick,” he said, but instead lasted up to a minute. Then, he said, Kelly “removed whatever was in me — to this day I’m not quite sure what he did, because he didn’t really explain it to me beforehand, during, or anything whatsoever.”

That experience, the man said, caused his life to spiral down as he isolated himself. He lost motivation. Medical records show that he gained weight. When he transferred to USC, he had a GPA of 4.0. By the time he graduated, his transcripts show, it had plummeted to a low of 2.85.

The effects of his appointment with Kelly played out slowly, he said. While he enjoyed some of his classes, he said he felt a growing resistance to the campus he had worked so hard to transfer to. The summer after his appointment with Kelly, he said, he went to New York for what he had planned as short trip, but ended up staying there for months. He said he considered dropping out, but his family ultimately convinced him to finish his degree.

“It really did take a lot out of me,” he said.

The cause of his spiral didn’t become clear to him until last year, he said, when he heard about the Los Angeles Times investigation of Tyndall. “You don’t realize what it’s like until years later and you have perspective, and you’re like, ‘Oh, so that’s why I was 70 pounds overweight, and that’s why I was really withdrawn and not seeing friends or family,’” he said. “It’s really messed up.” ●

Sasha Urban is a junior at the University of Southern California. He is originally from New York. Contact Sasha Urban at [email protected].

Source: Read Full Article